I inched back from the edge of the precipice, doing my best reverse Marine crawl, my chin never more than six inches from the deck.

It was at least 500 feet straight down into the crashing waves from where I had been peering over the edge of the sheer rock, lying on my belly. I gripped my camera tightly against the gale force winds.

When I got three or four feet back from the edge, I got up on my hands and knees and crawled backwards, away from the brink. The wind, a relatively calm gale when we first arrived, had unleashed its might in earnest, rocking me back and forth even with my four points of support and low center of gravity. As I was buffeted by the wind I was filled with the same sense of overwhelming angst, danger and awe that had permeated my being since we’d stepped over the wall separating the tourists from the raw reality of the Cliffs of Moher (photo 1).

Photo 1

As I scuttled to the cliff face that backed the rock shelf I had been shooting from, I heard two words that chilled my soul and literally stopped my heart.

“Doug, Help!”

These were the last words I wanted to hear while fighting the battering wind’s unwavering determination to sweep me into the sea so far below.

I was filled with dread, as my wife had an unending fascination with exploring the very edge of cliffs and high places, all in the pursuit of the perfect picture (see photo 2 for a typical example of her photo perching at a different location).

Photo 2

I had made her read the government warning sign regarding the constantly eroding cliffs and the precarious nature of the precipice before we crossed the line into the forbidden zone.

I had little faith it had made a lasting impression.

When I had last seen her, she was fitting her telephoto lens onto her camera. When I heard her scream, I had instant visions over her losing a battle against the battering gale and being swept over the rim, just out of my reach, her fingers clawing at the cold, bare rock, disappearing over the edge into a receding scream and the roar of the relentless wind.

As I rounded the cliff, my worst fears were not realized. I found her huddled against the cliff face, struggling to keep her camera bag, lenses and accessories within her grasp, her Windstopper gloves dancing toward the edge of the rock shelf.

“Forget the far one, forget it,” she screamed over the howl of the wind, as I half crawled toward the edge of the cliff and the quickly moving gloves.

Her two MSR GoreTex Windstopper gloves, perfect for protection against the unrelenting blast of the Atlantic wind, strengthened by thousands of miles of open sea and building momentum since it last touched land in Maine, were twitching in the wind, inching toward the cliff’s edge and the grasp of the frothing, insatiable sea pounding the base of the cliffs 500 feet below.

The closest glove lay a full four feet back from terror, the farthest was on a dance with death about six inches from the unforgiving edge of the escarpment.

I hopped to the nearest, crouching on all fours, snatching it as it rose to make a break for the freedom of the open air and welcoming embrace of the sea.

“Forget the other one!” she screamed, true fear, raw fear, fact fear, clear in her plea.

Our comfortable life receded into the distance as the life and death reality of the rock, the wind and the seductive siren song of the sea filled my senses.

The glove danced along the edge of the cliff.

Beckoning me. Calling me. Taunting me.

“Forget it,” she yelled, half pleading, half crying.

Her voice, her pleas, meant nothing to me now. It was between me and the sea, the wind and the glove. It was my chance to be her hero, and I was beyond recall. The gauntlet had been thrown, the warrior unleashed.

I dove toward the glove. For several milliseconds I was suspended above the rock shelf, a perfect parallel form, gliding above the flat rock toward the beckoning edge and the dancing glove. The brutal wind pushed me, shoved me, accelerated me towards the waiting embrace of the frigidly cold North Atlantic so far, far below.

Then I landed on the rock. My high speed mental calculations of launch strength, target distance, wind gust velocity and friction coefficient of the rock shelf and my clothing yielding an almost perfect result, my hand within inches of the glove. It was perfect. Except for one thing.

As I heard the Canon L series lens in my jacket pocket crunch between my body and the rock shelf I did a sub-second economic comparison of the value of the Windstopper glove within my grasp and the value of the lens grinding into the rock.

I grabbed the glove as it leapt one last time toward the edge, the breaking whitecaps of the hungry sea now visible below. I grasped it tightly, knowing full well it was the only four figure value glove on the cliffs that day.

**

We huddled against the cliff face, gathering our gear and the remnants of our composure around us.

I had spent the previous half hour shooting (photo 3), waiting for 250th of a second gaps in the wind, holding the tripod and camera strap in one hand and the remote shutter release in the other, feebly trying to capture the grandeur and majesty of the cliffs and their setting (photo 4). As with many places we see on our travels, we were torn between the overwhelming despair of “why even attempt to capture this” and the challenge to grab some small essence of the place and time.

Photo 3

Photo 4

The wind, by and large, had defeated us. An ever-present, gusting constant during our travels up the West coast of Ireland, it had turned from a presence upon our arrival at the cliffs to a true menace. We retreated from the rock shelf we had been perched on toward the grassy cliffs that ran parallel to the coast. On our way there, I realized, to my horror, I had set my glasses down on the rocks when I had framed up the first shot, at least an hour before.

We rushed across the rock shelf to the area where I had been shooting, hoping that my glasses had been blown into a crevice or some other safe spot. A quick survey of the area yielded only bare rock and a few hardy plants desperately clinging to the cracks of existence yielded by the rocks and the wind.

I searched the rock closely. I even lay down and peeked over the edge, searching in vain the small ledges below the main rock shelf I had been shooting from an hour before, my tripod legs a score of unconfident inches from the edge.

Just as I was about to abandon the search, I heard a faint metallic rattle mixed with the brief pauses in the monumental wind. It was the only unnatural sound in the cacophony of the roar of the wind, the sea was much too far below to be heard in the gale.

I looked around to my right. There they were! They were about twenty feet out, on their backs, skittering across the rock shelf, dizzily dancing before the gusts.

I couldn’t believe my good fortune in finding them. Could I retrieve them? Could I in some way make up for the monumental stupidity of setting them down and abandoning them on this wind scoured rock shelf?

For the second time in an hour, I did a dance of death with the rocks, the wind and the sea.

First left, then right, then left again they danced. The wind laughed at me; it scoffed at my human inadequacy, frailty and fear. Just out of my reach my glasses slid toward the edge of the cliffs.

No! Not this close, not after this much time, not after an hour of jittering around on this cliff could they blow off into the ocean while I watched.

They faked right, they broke left. I hopped on all fours left, lunged toward the edge and grabbed them.

I had cheated death twice in one day.

Two times I had seen my hand grasping the prize, suspended over the cliff’s edge with the breaking surf in the background.

I had had enough.

But the wind had not.

**

We picked up our bags and made our way to the grass topped cliff, perpendicular to the rock shelf we had been on for what now seemed days. We started the long walk along the cliffs for a reverse view, with O’Brien’s tower castle perched on the point (photo 5).

Photo 5

Suddenly, the wind, seeking its revenge, picked us both up like leaves on a lawn and blew us down the slope. This wind was like no other in my life. Never, in all my years of Iowa blizzards and Chicago Hawks, had I been literally blown off my feet. If we had been along the cliff’s edge when it hit, in any position other than lying down, we would have been swept off by its ferocity.

Shaken, but alive, we picked ourselves up and made a bee-line for the car. The Atlantic winds of the Cliffs of Moher had reminded us who was the force and who was the pretender.

I felt lucky to be alive.

**

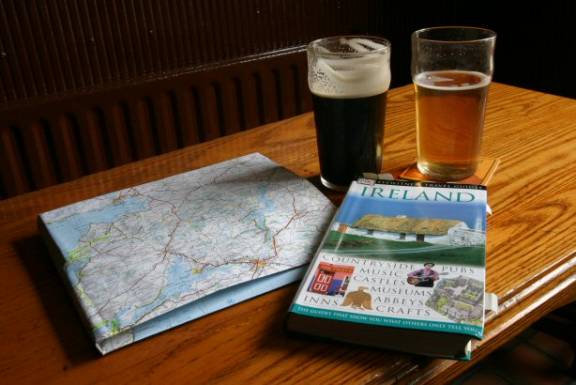

We retired to the first local pub we came across. Like every other pub in the West of Ireland, it offered a warm, cheery fire (photo 6) and cool pints of stout and lager (photo 7).

Photo 6

Photo 7

We held our glasses with trembling hands, toasted our good fortune to escape with our lives, and there learned that three days before a woman had been blown from the cliffs to the cold sea below. Saddened, we offered our prayers to her family and friends, and were reminded of the temporary nature of life, of the blessings of good fortune, and the treasure of loved ones, close and dear.

May you be so blessed.

Be well,

Doug

PS – Ireland remains a country of unsurpassed natural beauty, fascinating history and profoundly welcoming people.

In our two week One Lap Of Ireland we learned that my friend Jerry O’Brien is the descendant of the first high king of Ireland, Brian Boru. Jerry, like all of his clan, is “of Brian,” or O’Brien, in the modern form. Here we found the homeland of my wife’s ancestors, the O’Donohues, she being half German and half Irish (I will leave you to ponder the profound implications of that lineage).

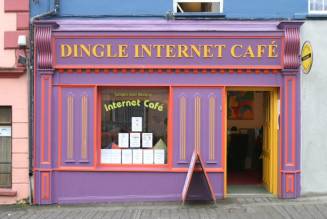

We also viewed ancient ruins (photos 8 & 9), drove down small lanes (photo 10), past charming thatched roof cottages (photo 11) (including the thatcher (photo 12)), countless pubs with traditional Irish musicians (photo 13), bravely painted shops (photos 14 - 16), weavers (photo 17), lighthouses (photo 18), simple country life (photo 19), peat bogs (photo 20), birds of prey (photo 21), rugged beauty (photo 22), sleepy fishing villages (photo 23), Medieval ruins (photo 24-26), charming B&Bs (photo 27), examples of profound faith (photo 28) and contemplated stunningly idyllic scenes (photo 29).

Ireland awaits.

But hurry. It is fast developing, and the authentic Ireland can not long resist the tide of McDonalds and Starbucks sweeping all before it (although we saw only two of the former and none of the latter in all our time here, during which we studiously avoided developed areas).

Photo 8

Photo 9

Photo 10

Photo 11

Photo 12

Photo 13

Photo 14

Photo 15

Photo 16

Photo 17

Photo 18

Photo 19

Photo 20

Photo 21

Photo 22

Photo 23

Photo 24

Photo 25

Photo 26

Photo 27

Photo 28

Photo 29